Hydraulic pistons serve as the fundamental force-generating components in fluid power systems across industries ranging from construction equipment to aerospace applications. When engineers and procurement managers search for information about hydraulic piston types, they're typically working to match the right actuator configuration to specific load requirements, speed parameters, and environmental conditions. This guide breaks down the core classifications of hydraulic pistons based on operating principles and structural geometry, helping you make informed decisions about which type fits your application.

The Foundation: How Hydraulic Pistons Generate Force

Before examining different hydraulic piston types, it's essential to understand the basic mechanism. A hydraulic piston operates inside a cylinder barrel filled with incompressible hydraulic oil. The piston divides the cylinder into two chambers—the cap end and the rod end. When pressurized fluid enters one chamber, it pushes against the piston's surface area, converting hydraulic pressure into linear mechanical force according to Pascal's Law.

The relationship between pressure and force is straightforward. If you know the system pressure (P) and the piston bore diameter (D), you can calculate the theoretical output force using the piston area. For a circular piston, the area equals π × D² ÷ 4. This means a 4-inch bore piston operating at 3,000 PSI generates approximately 37,700 pounds of force on the extension stroke. The actual delivered force will be slightly lower due to friction losses in the seals and guide rings, which typically account for 3-8% efficiency reduction depending on seal material and groove geometry.

The incompressibility of hydraulic oil makes these systems particularly valuable in safety-critical applications. In aircraft landing gear systems, for example, the fluid maintains consistent control authority even when ambient pressure changes dramatically during flight. This characteristic allows hydraulic piston types to deliver high power density with precise control—a combination difficult to achieve with pneumatic or purely mechanical systems.

Primary Classification: Single-Acting vs. Double-Acting Hydraulic Piston Types

The most fundamental way to categorize hydraulic piston types is by how fluid pressure drives the motion. This classification directly impacts control capability, speed, and system complexity.

Single-Acting Cylinders: Simplicity and Reliability

Single-acting cylinders use pressurized fluid to drive the piston in only one direction—typically extension. The piston retracts through an external force, which might be a compressed spring inside the cylinder, gravity acting on the load, or an external mechanism pushing the rod back in. You'll find single-acting designs in hydraulic jacks, simple lift cylinders, and press applications where the return stroke doesn't require controlled force.

The engineering advantage of single-acting hydraulic piston types lies in reduced component count. With only one fluid port and no need for seals and passages on both sides of the piston, these cylinders cost less to manufacture and maintain. Fewer moving parts mean fewer potential failure points, which explains why single-acting cylinders remain popular in applications where uptime is critical but bidirectional control isn't necessary.

However, the limitation is clear: you cannot control retraction speed or force precisely because it depends entirely on the external mechanism. If your application needs a fast, controlled return stroke, a single-acting cylinder won't meet the requirement. The retraction speed is determined by whatever external force is available, whether that's a spring's stored energy or the weight of the load being lowered.

Double-Acting Cylinders: Precision and Bidirectional Control

Double-acting hydraulic cylinders represent the more versatile category of hydraulic piston types. These cylinders have two fluid ports, allowing pressurized oil to enter either side of the piston. When fluid flows into the cap end, the piston extends. Reverse the flow direction, sending fluid into the rod end, and the piston retracts under controlled hydraulic pressure.

This bidirectional hydraulic control provides several operational benefits. First, both extension and retraction happen at speeds determined by fluid flow rate rather than external forces, enabling predictable cycle times. Second, the system can generate substantial pulling force during retraction, not just pushing force during extension. For equipment like excavator arms, lift platforms, and manufacturing presses, this pulling capability is often just as important as pushing capability.

Double-acting hydraulic piston types also maintain consistent force throughout the stroke length, assuming constant pressure and flow. This uniformity matters in precision manufacturing processes where the load must move at steady velocity regardless of position. The trade-off is increased complexity. Double-acting cylinders require more sophisticated valve systems to control bidirectional flow, additional seals to handle pressure on both piston faces, and typically cost 30-50% more than comparable single-acting designs.

One technical detail worth noting: in a double-acting cylinder with a single rod extending from one end, the effective areas on each side of the piston differ. The cap end has the full bore area, but the rod end has the bore area minus the rod cross-section. This area difference means extension and retraction speeds will differ at the same flow rate, and the extension force will be higher than retraction force at the same pressure. Engineers must account for this asymmetry during system design, either by accepting the speed difference or by using flow control valves to balance velocities.

| Characteristic | Single-Acting Cylinder | Double-Acting Cylinder |

|---|---|---|

| Fluid Ports | One port, one active chamber | Two ports, two active chambers |

| Force Direction | Unidirectional (push only) | Bidirectional (push and pull) |

| Retraction Method | External force (spring, gravity, load) | Hydraulic pressure controlled |

| Control Precision | Limited (uncontrolled retraction) | High (full control of both directions) |

| Complexity & Cost | Simple, economical | Complex, higher cost |

| Typical Applications | Jacks, simple lifts, presses | Excavators, lifts, precision machinery |

Specialized Structural Types: Geometry-Based Hydraulic Piston Classifications

Beyond the basic single-acting and double-acting distinction, hydraulic piston types also divide into specialized structural configurations. Each geometry solves specific engineering challenges related to force output, stroke length, or installation space.

Plunger (Ram) Cylinders: Maximum Force in Compact Designs

Plunger cylinders represent one of the most straightforward hydraulic piston types in terms of construction. Instead of having a separate piston head that travels inside the cylinder, a plunger cylinder uses a solid ram that extends directly from the cylinder barrel. This ram acts as both the piston and the rod, pushing against the load as it extends.

The engineering benefit comes from simplicity. With no separate piston assembly, there are fewer seals to maintain and less internal volume to fill with fluid. Plunger cylinders typically operate as single-acting units, extending under hydraulic pressure and retracting by gravity or an external spring. This makes them ideal for vertical lifting applications where the load's weight provides the return force.

Plunger hydraulic piston types excel in situations requiring high force output from a relatively compact cylinder body. Because the entire rod diameter serves as the pressure-bearing area, you can achieve forces comparable to larger bore cylinders while using less installation space. Hydraulic presses, heavy-duty jacks, and forge presses commonly use plunger designs. In offshore drilling ships, plunger cylinders handle the enormous forces needed to position drill strings, where their robust construction withstands harsh marine environments.

Differential Cylinders: Leveraging Area Asymmetry

Differential cylinders are essentially double-acting cylinders with a single rod extending from one end, but engineers use this term specifically when discussing circuits that exploit the area difference between the two piston faces. The cap end has the full bore area, but the rod end has an annular area equal to the bore area minus the rod area.

This asymmetry creates different speeds and forces depending on direction. During extension at a given flow rate, the piston moves more slowly because fluid fills the larger cap-end volume. During retraction, the smaller rod-end volume means faster piston speed at the same flow rate. Some applications intentionally use this characteristic—for example, a mobile crane might need slow, powerful extension to lift a load, then faster retraction to reset for the next cycle.

Differential hydraulic piston types become particularly interesting when configured in regenerative circuits. In this setup, the fluid exiting the rod end during extension feeds back to join the pump flow entering the cap end, rather than returning directly to tank. This regenerated flow effectively increases the total volume entering the cap end, significantly boosting extension speed during light-load or no-load conditions. The trade-off is reduced available force, since the pressure differential across the piston decreases. Engineers typically use regenerative circuits for rapid approach movements, then switch to standard operation when full force is needed for the work phase.

Mobile hydraulic equipment like excavators and material handlers rely heavily on differential cylinder designs. The ability to achieve variable speed characteristics without additional valving simplifies the hydraulic circuit while maintaining the versatility needed for complex work cycles.

Telescopic (Multi-Stage) Cylinders: Maximum Stroke from Minimum Space

Telescopic cylinders address a specific engineering challenge: achieving long extension strokes from cylinders that must fit in limited space when retracted. These hydraulic piston types use nested tubes of progressively smaller diameters, somewhat like a collapsing telescope. The largest tube forms the main barrel, and each successive stage nests inside, with the smallest innermost stage serving as the final plunger.

When pressurized fluid enters, it first extends the innermost stage. As that stage reaches its limit, it pushes the next larger stage outward, creating a smooth, sequential extension. Depending on the application, telescopic cylinders can have three, four, five, or even more stages. A five-stage telescopic cylinder might retract to 10 feet but extend to 40 feet or more.

The key specification for telescopic hydraulic piston types is the stroke-to-collapsed-length ratio. A conventional single-stage cylinder's collapsed length equals the stroke plus the necessary mounting and sealing space—often a 1:1 ratio at best. Telescopic designs routinely achieve 3:1 or 4:1 ratios, making them indispensable for dump trucks, aerial work platforms, and crane booms where extended reach is essential but retracted dimensions must remain compact for transport and storage.

Material selection varies by application. Aluminum telescopic cylinders serve lightweight aerial platforms where reducing reciprocating mass improves cycle time and energy efficiency. Heavy-duty steel versions handle the brutal conditions in mining dump trucks and mobile cranes, where impact loads and environmental exposure demand maximum durability. Aerospace applications use telescopic hydraulic piston types for cargo door actuation, benefiting from the high stroke-to-length ratio while meeting strict weight requirements through aluminum construction with corrosion-resistant surface treatments.

Tandem Cylinders: Force Multiplication Through Series Connection

Tandem cylinders connect two or more pistons in series along a common centerline, joined by a single continuous rod. Pressurized fluid enters both chambers simultaneously, pushing both pistons against the shared rod. This arrangement effectively doubles the force output compared to a single cylinder of the same bore diameter.

The force multiplication principle is straightforward. If each piston has an area of A square inches and system pressure is P PSI, a single piston generates force F = P × A. With two pistons in tandem, total force becomes F = P × (A + A) = P × 2A, doubling the output without requiring a larger bore diameter or higher pressure. For applications where space constraints limit bore size but required force exceeds what a single piston can deliver, tandem hydraulic piston types offer a practical solution.

Beyond force multiplication, tandem configurations provide improved stability and precision during motion. The dual piston arrangement naturally resists side loading better than a single long piston would, reducing the risk of seal wear from misalignment. This makes tandem cylinders suitable for precision positioning tasks in manufacturing presses and assembly equipment.

Safety-critical aerospace applications value the inherent redundancy in tandem hydraulic piston types. Aircraft landing gear systems sometimes use tandem configurations where each chamber can function independently. If one chamber experiences a pressure loss or seal failure, the other chamber can still generate meaningful force to deploy or retract the gear, providing a level of fault tolerance that simple cylinders cannot match. This redundancy comes at the cost of increased length, weight, and complexity, but for systems where failure isn't acceptable, the trade-off is justified.

| Type | Operating Mode | Key Structural Feature | Primary Advantage | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plunger (Ram) | Single-acting | Solid ram serves as piston | Maximum force density, robust construction | Hydraulic jacks, forge presses, vertical lifts |

| Differential | Double-acting | Single rod, asymmetric piston areas | Variable speed characteristics, regenerative circuit capability | Mobile cranes, excavators, industrial robots |

| Telescopic | Single or double-acting | Nested stages, sequential extension | Maximum stroke from minimum collapsed length (3:1 to 5:1 ratio) | Dump trucks, aerial platforms, crane booms |

| Tandem | Double-acting | Two pistons in series on shared rod | Force multiplication, enhanced stability, inherent redundancy | Heavy presses, aircraft landing gear, precision positioning |

Performance Engineering: Calculating Force and Speed Parameters

Understanding the theoretical performance of different hydraulic piston types requires quantitative analysis of force output and speed characteristics. These calculations form the foundation of proper cylinder sizing and system design.

The force equation is fundamental to all hydraulic piston types. Extension force equals pressure multiplied by piston area: F = P × A. For a piston with bore diameter D, the area is A = π × D² ÷ 4. In practical units, if D is measured in inches and P in PSI, force F comes out in pounds. For example, a 3-inch bore piston at 2,000 PSI delivers F = 2,000 × (3.14159 × 9 ÷ 4) = approximately 14,137 pounds of push force.

Retraction force calculations must account for the rod area. If the rod diameter is d, the effective rod-end area becomes A_rod = π × (D² - d²) ÷ 4. At the same pressure, retraction force equals F_retract = P × A_rod. This is why double-acting hydraulic piston types with asymmetric rods always pull with less force than they push, a factor that must be considered during load analysis.

Speed calculations depend on flow rate and effective area. If the pump delivers Q gallons per minute into a piston area A (in square inches), the extension velocity V in inches per minute equals V = 231 × Q ÷ A. The constant 231 converts gallons to cubic inches (one gallon equals 231 cubic inches). This relationship shows why retraction speed exceeds extension speed in differential cylinders—the smaller rod-end area means the same flow rate produces higher velocity.

Consider a practical example comparing single-acting and double-acting hydraulic piston types. A 4-inch bore cylinder with a 2-inch rod operates at 2,500 PSI with 15 GPM flow. The cap-end area is 12.57 square inches, and the rod-end area is 9.42 square inches. Extension force is 31,425 pounds, and retraction force is 23,550 pounds. Extension speed is 276 inches per minute, while retraction speed is 368 inches per minute. If this were a single-acting cylinder relying on a spring for retraction, the return speed would depend entirely on the spring constant and load weight, making it unpredictable and generally slower.

Selecting the Right Hydraulic Piston Type for Your Application

Choosing between different hydraulic piston types requires matching technical capabilities to application requirements. This decision impacts performance, reliability, maintenance costs, and system complexity.

For applications requiring unidirectional force with predictable load characteristics, single-acting hydraulic piston types offer the most economical and reliable solution. Hydraulic presses that push material through a forming die don't need powered return strokes—gravity or a return spring suffices. Similarly, vertical lifting jacks benefit from single-acting designs because the load's weight naturally retracts the cylinder. The simplicity means fewer seals to fail, reduced valve complexity, and lower overall system cost.

When bidirectional control is essential, double-acting cylinders become necessary. Excavator bucket cylinders must pull with controlled force to curl the bucket closed and push with controlled force to dump material. Lift tables need to lower loads at safe, regulated speeds rather than dropping under gravity. Manufacturing automation requires precise positioning in both directions. These applications justify the additional cost and complexity of double-acting hydraulic piston types because the functional requirements cannot be met otherwise.

Differential cylinders suit applications where variable speed characteristics provide an advantage. Mobile equipment often benefits from fast approach speeds during unloaded travel, then slower speeds under load. Regenerative circuits can achieve rapid extension during positioning phases, then switch to standard operation during work phases, optimizing cycle time without requiring variable-displacement pumps or complex proportional valving.

Space constraints drive the selection of specialized structural types. When stroke length must exceed three times the available envelope for the retracted cylinder, telescopic hydraulic piston types become the only practical option. Aerial work platforms, fire truck ladders, and stadium retractable roofs all depend on telescopic designs to achieve the necessary reach from compact storage positions.

Force requirements beyond what standard bore sizes can deliver may necessitate tandem hydraulic piston types or plunger designs. Forge presses generating thousands of tons of force often use multiple tandem cylinders arranged in parallel. Plunger cylinders provide maximum force density when the application permits vertical orientation and gravity return.

Environmental factors influence material and seal choices within any hydraulic piston type. Marine applications require corrosion-resistant coatings and seals compatible with saltwater exposure. High-temperature manufacturing processes need seals rated for continuous operation above 200°F. Food processing equipment must use FDA-approved seal materials and surface finishes that won't harbor bacteria.

Advanced Sealing Systems and Friction Management

The reliability and lifespan of all hydraulic piston types depend heavily on seal design and material selection. Seals prevent fluid leakage, exclude contaminants, and manage friction between moving components. Understanding seal technology is essential for maintaining long-term cylinder performance.

Rod seals prevent pressurized fluid from escaping past the rod where it exits the cylinder. Low-pressure applications typically use lip seals, which have a flexible sealing edge that contacts the rod surface through mechanical interference and fluid pressure. These work well up to approximately 1,500 PSI. Higher-pressure systems require U-cup seals, which have a U-shaped cross-section that allows fluid pressure to energize the sealing lips. As pressure increases, the seal spreads against both the rod and groove, creating a tighter seal automatically.

Seal material selection significantly impacts performance across different hydraulic piston types. Polyurethane (PU) dominates industrial applications due to excellent wear resistance and pressure capability. Specialized high-hardness polyurethane formulations can handle pressures exceeding 4,000 PSI in heavy mobile equipment. The typical temperature range for PU seals runs from -45°C to 120°C, covering most industrial environments. The limitation is susceptibility to hydrolysis in high-temperature water-based fluids.

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) excels in chemical compatibility and low friction. PTFE seals resist virtually all hydraulic fluids and corrosive media, making them ideal for chemical processing equipment and high-temperature applications. The material functions across an extreme temperature range from -200°C to 260°C theoretically, though practical limits usually depend on elastomeric energizer rings that work with PTFE elements. The low friction coefficient means PTFE seals reduce stick-slip behavior and improve efficiency in precision positioning applications.

Polyether ether ketone (PEEK) represents the premium seal material for extreme conditions. PEEK outperforms PTFE in applications involving high mechanical stress, high pressure, or severe wear. The material exhibits superior creep resistance under sustained load and maintains structural integrity at temperatures where other plastics fail. PEEK seals cost significantly more than PU or PTFE, but in safety-critical aerospace applications or heavy industrial presses where seal failure could be catastrophic, the investment is justified.

Seal groove geometry affects dynamic friction as much as material choice. Research shows that groove dimensions directly influence contact pressure distribution across the seal face. When groove depth decreases, maximum contact pressure between seal and rod can increase from 2.2 MPa to 2.5 MPa, substantially changing friction behavior. Manufacturing tolerances on the cylinder bore also impact friction consistency. If bore straightness and roundness vary beyond specification, the seal experiences varying contact pressure during stroke, potentially causing stick-slip motion at low speeds.

Friction in hydraulic piston types consists of several components: seal friction, guide ring friction, and fluid drag. Seal friction typically dominates, accounting for 60-80% of total resistance. Proper seal design balances sealing effectiveness against friction losses. Excessive contact pressure ensures leak-free operation but increases heat generation, accelerates wear, and reduces efficiency. Insufficient contact pressure reduces friction but allows leakage and admits contamination. Advanced finite-element analysis during seal groove design helps optimize this balance for specific applications.

| Material | Maximum Pressure Rating | Operating Temperature Range | Key Advantages | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyurethane (PU) | Up to 4,000+ PSI | -45°C to 120°C | Excellent wear resistance, high pressure capability, economical | Industrial machinery, mobile equipment, general hydraulics |

| PTFE | High (requires energizer) | -200°C to 260°C (practical limits vary) | Extreme chemical compatibility, lowest friction coefficient | Chemical processing, high-temperature systems, precision positioning |

| PEEK | Extremely high | Wide range, excellent high-temp stability | Superior mechanical strength, creep resistance, extreme conditions | Aerospace actuation, heavy industrial presses, safety-critical systems |

| NBR (Nitrile) | Moderate | -40°C to 120°C | Good general compatibility, widely available, low cost | Standard hydraulic equipment, general industrial use |

Stroke-End Control: Cushioning Systems in Dynamic Applications

High-speed operation of hydraulic piston types generates substantial kinetic energy that must be safely dissipated at stroke end. Without proper cushioning, the piston impacts the end cap violently, creating shock loads that damage components, generate noise, and reduce system lifespan.

Cushioning systems work by restricting fluid flow as the piston approaches stroke end. A tapered spear or plunger enters a mating pocket in the end cap, progressively reducing the exit flow area. The trapped fluid must then escape through a fixed orifice or adjustable needle valve, creating backpressure that slows the piston smoothly. A check valve typically allows free flow during direction reversal to avoid restricting acceleration.

Two main cushioning designs appear in different hydraulic piston types. Spear-type cushions use an elongated tapered element extending from the piston or rod that enters the end cap pocket. The annular clearance between spear and pocket, combined with the adjustable needle valve, controls deceleration rate. This design requires significant space in the end cap for the pocket and valve assembly. Piston cushions instead use a cast iron ring on the piston itself, working with a precisely sized orifice in the end cap. This approach saves space but offers less adjustment flexibility.

Adjustable cushions let operators tune deceleration characteristics to match load and speed. However, this also introduces risk. If operators chase productivity by minimizing cushion restriction, they may not realize they're trading long-term reliability for short-term cycle time improvements. Fixed cushions eliminate this risk but cannot adapt to varying conditions.

Pressure intensification becomes a concern during the final cushioning phase. As the piston compresses fluid in the shrinking volume, pressure can spike well above system pressure, especially at high velocities. Cylinder end caps and seals must be rated to handle these transient pressure peaks, not just the nominal operating pressure. This factor becomes critical in high-cycle-rate applications like automated manufacturing lines where millions of cushioned stops occur annually.

Looking Forward: Emerging Trends in Hydraulic Piston Technology

The development of hydraulic piston types continues to advance as manufacturers integrate smart technologies, advanced materials, and sophisticated control systems. Understanding these trends helps engineers specify systems that will remain competitive and serviceable for years.

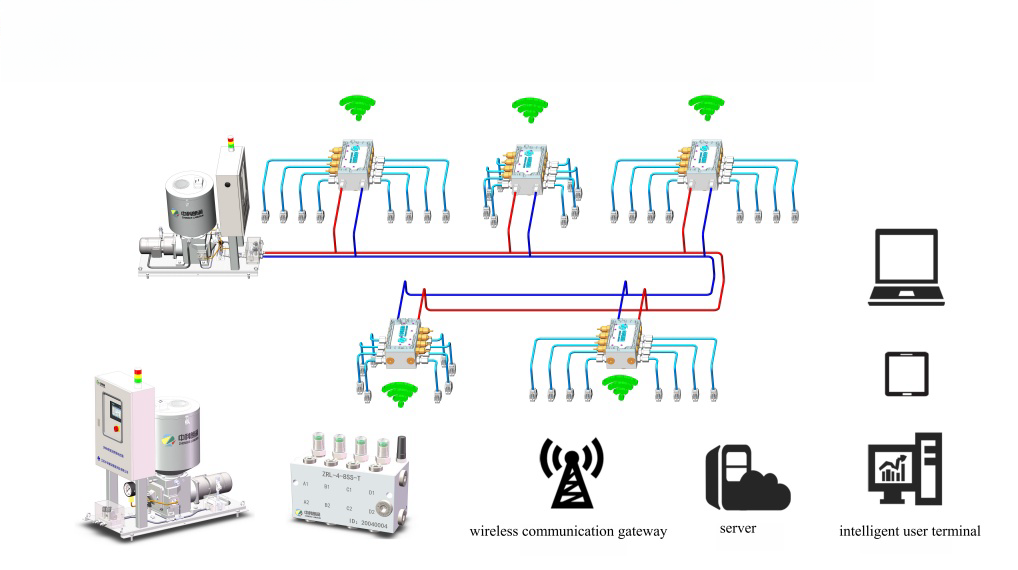

Smart cylinder integration represents the most significant current trend. Hydraulic cylinders traditionally functioned as passive mechanical components, but modern variants incorporate magnetostrictive position sensors that provide absolute position feedback without recalibration after power loss. These sensors generate continuous electronic signals indicating exact rod position, enabling closed-loop control and automated operation. The non-contact sensing principle eliminates wear, ensuring consistent accuracy over millions of cycles.

Adding IoT connectivity to position sensing creates predictive maintenance capabilities. Sensors monitoring pressure, temperature, and cycle count throughout the hydraulic system generate data streams that reveal developing problems before failure occurs. A gradual increase in operating temperature might indicate seal wear or contamination. Pressure fluctuations during extension could signal valve malfunction or fluid aeration. Remote monitoring systems alert maintenance teams to these conditions while equipment is still operational, preventing unexpected downtime.

Material science advances are reducing weight while maintaining strength in hydraulic piston types. High-strength aluminum alloys replace steel in applications where weight reduction justifies the higher material cost. Aerospace and mobile equipment particularly benefit from lighter cylinders because reduced mass improves fuel efficiency and payload capacity. Surface treatments on aluminum components—anodizing, nickel-plating, or specialized coatings—provide corrosion resistance comparable to steel.

Manufacturing processes now achieve tighter tolerances on bore straightness, roundness, and surface finish. Improved bore quality directly translates to better seal performance and reduced friction. Honing processes can now produce Ra surface finishes below 0.2 micrometers, minimizing seal wear and extending service life. Laser measurement systems verify dimensional accuracy to microns, ensuring consistent quality across production runs.

Rod surface treatments have evolved beyond traditional chrome plating. High-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF) spraying deposits extremely hard, wear-resistant coatings. Laser cladding fuses protective alloys to rod surfaces, creating metallurgical bonds superior to plating. These advanced treatments resist corrosion and abrasion better than chrome while avoiding the environmental concerns associated with hexavalent chromium plating processes.

Digital twin technology is changing how manufacturers develop and test hydraulic piston types. Creating a virtual model of a cylinder allows engineers to simulate performance under various conditions without building physical prototypes. Finite element analysis examines stress distribution in critical components. Computational fluid dynamics reveals flow patterns and pressure drops within complex porting geometries. These virtual tools accelerate development cycles and enable optimization that would be impractical through physical testing alone.

Hybrid power systems are emerging that combine hydraulic and electric actuation. Some applications benefit from hydraulic power density for heavy work phases but prefer electric actuation for precise positioning or light-load movement. Developing cylinders that integrate with these hybrid architectures requires rethinking traditional hydraulic piston types to accommodate electronic control interfaces and regenerative energy recovery.

Making the Right Choice for Your System

Successfully applying hydraulic piston types to real-world systems requires balancing multiple technical and economic factors. The simplicity and reliability of single-acting cylinders make them ideal when load characteristics naturally provide return force and retraction speed isn't critical. Double-acting cylinders are essential when applications demand controlled bidirectional force and speed, accepting the additional cost and complexity.

Specialized geometries address specific constraints. Plunger cylinders maximize force output in compact installations. Telescopic designs solve long-stroke requirements in limited space. Tandem configurations multiply force without increasing bore size or pressure. Differential cylinders with regenerative circuits optimize speed and force characteristics for varying load conditions.

Seal selection impacts long-term reliability as much as cylinder type. Match seal material to fluid type, temperature range, and pressure levels. Consider that PEEK outperforms other materials in extreme mechanical stress environments, while PTFE excels in chemical compatibility and friction reduction. Remember that groove geometry and manufacturing tolerances affect seal performance as much as material properties.

As hydraulic piston types evolve with embedded sensors and IoT connectivity, prioritize systems that support predictive maintenance and remote monitoring. The incremental cost of smart cylinders is often recovered through reduced downtime and optimized maintenance scheduling. Evaluate suppliers based on their ability to provide not just mechanical components but integrated solutions with proper control interfaces and diagnostic capabilities.

The hydraulic piston remains a fundamental element in industrial automation, mobile equipment, and manufacturing systems. Understanding the operational principles, structural variations, and performance characteristics of different hydraulic piston types enables informed decisions that optimize system performance while controlling costs. Whether you're designing a new system or upgrading existing equipment, matching the right cylinder type to your specific requirements ensures reliable operation and long service life.