When you work with hydraulic or pneumatic systems, understanding proportional valve diagrams becomes essential for designing, troubleshooting, and maintaining modern automation equipment. A proportional valve diagram shows how these precision components control fluid flow and pressure in response to electrical signals, bridging the gap between electronic control systems and mechanical motion.

Unlike simple on-off valves that can only be fully open or fully closed, proportional valves offer variable control anywhere between 0% and 100% opening. This continuous adjustment capability makes them critical for applications requiring smooth acceleration, precise positioning, and controlled force application. The diagrams we use to represent these valves follow standardized symbols defined primarily by ISO 1219-1, creating a universal language that engineers worldwide can understand.

What Makes a Proportional Valve Diagram Different

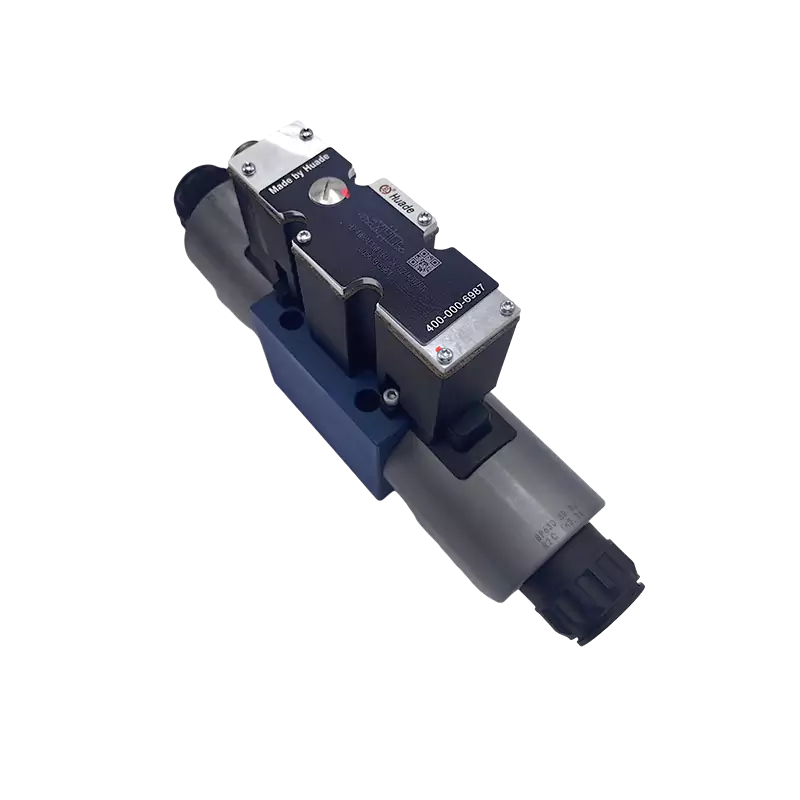

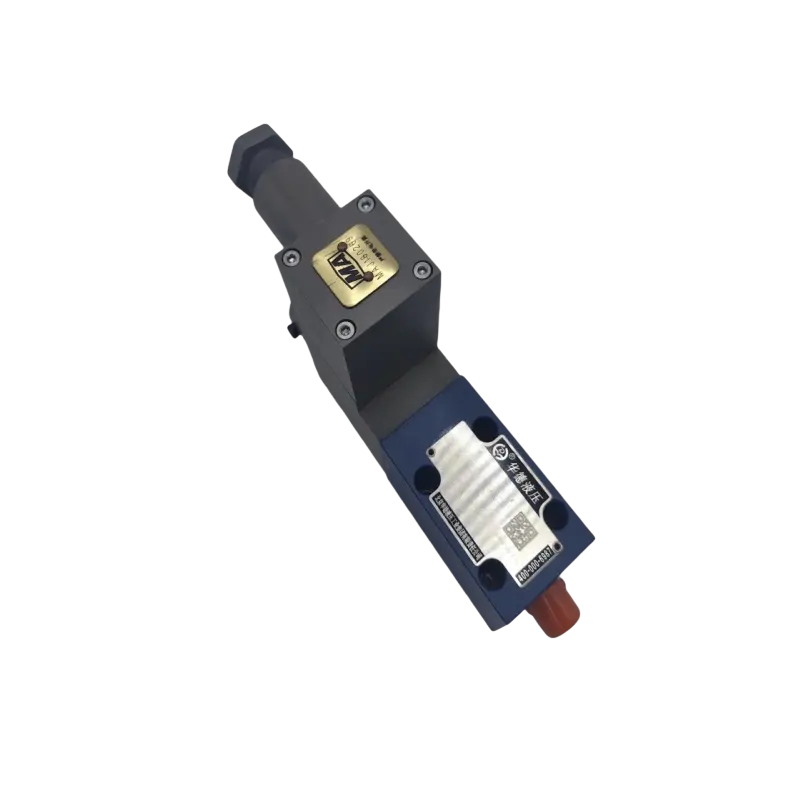

A proportional valve diagram contains specific symbolic elements that immediately distinguish it from standard valve symbols. The most recognizable feature is the proportional actuator symbol, which consists of an electromagnetic coil enclosed in a box with two parallel diagonal lines crossing through it. These diagonal lines are the key identifier that tells you this valve provides proportional control rather than simple switching.

When you see a small dashed triangle near the proportional solenoid symbol, this indicates the valve has onboard electronics (OBE). These integrated electronic components handle signal processing, amplification, and often feedback control functions directly within the valve body. This integration simplifies installation by reducing the need for external amplifier cabinets and associated wiring complexity.

The valve envelope itself shows multiple positions, typically depicted as a three-position, four-way valve (4/3 configuration). Unlike standard directional control valves, proportional valve diagrams often show the center position with partially aligned flow paths, indicating the valve's ability to meter flow continuously rather than simply blocking or fully opening ports.

Reading ISO 1219-1 Proportional Valve Symbols

The ISO 1219-1 standard provides the framework for hydraulic and pneumatic circuit diagrams. For proportional valves, this standard defines how to represent different valve types and their control mechanisms. A proportional directional control valve symbol includes the basic valve body with metering notches or triangular symbols within the flow paths, indicating specially machined features that enable precise flow control.

These machined features, often triangular notches cut into the valve spool, are critical for achieving high flow sensitivity and linearity near the zero position. Without these geometric modifications, the valve would exhibit poor control characteristics when making small adjustments from the closed position.

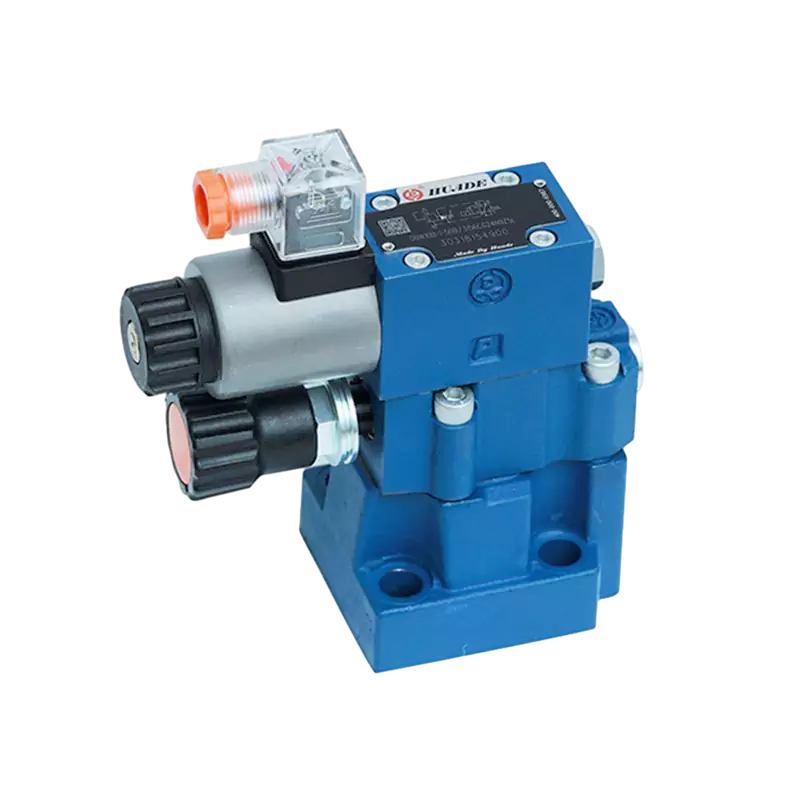

Proportional pressure control valves, such as proportional relief valves or reducing valves, use similar symbolic conventions. The main difference lies in the addition of the proportional solenoid actuator and the pressure control spring symbol. When you see these elements combined with the dashed triangle indicating OBE, you know you're looking at a sophisticated, closed-loop pressure control device.

Proportional flow control valves are typically symbolized as two-position, two-way valves or variable orifices, always marked by the characteristic proportional control actuator. These valves work with air, gases, water, or hydraulic oil, making them versatile components in industrial automation.

How Proportional Valves Work: The Electro-Hydraulic Conversion

The fundamental principle behind proportional valve operation involves converting an electrical signal into precise mechanical movement. When you send a control signal (typically 0-10V or 4-20mA) to the valve, it passes through the onboard electronics to a proportional solenoid. The solenoid generates a magnetic field proportional to the input current, which moves an armature or plunger connected to the valve spool or poppet.

Many modern proportional valves use pulse width modulation (PWM) control. In PWM systems, the control electronics rapidly switch the voltage to the solenoid coil on and off. By adjusting the duty cycle (the ratio of on-time to total cycle time), the valve achieves precise position control while the high-frequency switching (often around 200 Hz) helps overcome static friction in the moving parts.

This PWM dither signal serves an important purpose beyond basic control. Static friction between the valve spool and bore can cause sticking and poor response at low signal levels. The continuous high-frequency vibration from dither effectively converts static friction into lower dynamic friction, significantly reducing dead band and improving responsiveness. However, this rapid motion creates viscous damping forces that require careful design compensation through pressure sensing tubes and balanced internal geometry.

| Valve Type | Opening Range | Control Method | Typical Response Time | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On/Off (Discrete) | 0% or 100% only | Switch actuation | 10-50 ms | Low |

| Proportional Valve | Variable 0-100% | PWM/Current with LVDT feedback | 100-165 ms | Medium |

| Servo Valve | Variable with high dynamics | Voice coil/torque motor with high-resolution feedback | 5-20 ms | High |

The performance gap between proportional valves and servo valves has narrowed considerably. Modern proportional valves with integrated LVDT (Linear Variable Differential Transformer) feedback achieve hysteresis typically below 8% and repeatability within 2%. This level of performance allows proportional valves to handle many applications that once required expensive servo valves, at roughly half the cost.

Direct-Acting vs Pilot-Operated Designs

When you examine proportional valve diagrams more closely, you'll notice structural differences that indicate whether the valve uses direct-acting or pilot-operated design. This distinction significantly affects the valve's flow capacity and pressure rating.

In a direct-acting proportional valve, the electromagnetic armature connects directly to the valve spool or poppet. The solenoid force moves the metering element without hydraulic assistance. This direct connection provides excellent control precision and fast response times, typically achieving step response times around 100 milliseconds for NG6 (CETOP 3) mounting interface sizes. However, the limited force output from proportional solenoids restricts direct-acting designs to moderate flow rates and pressures.

Pilot-operated proportional valves overcome these limitations by using the working fluid itself to assist in moving the main valve spool. The proportional solenoid controls a small pilot stage, which directs pressurized fluid to act on the larger main spool. This hydraulic amplification allows pilot-operated valves to handle substantially higher flow rates and pressures, often reaching 315 to 345 bar (4,500 to 5,000 PSI). Applications like tunnel boring machine thrust systems and heavy mobile equipment commonly use pilot-operated proportional valves for this reason.

The tradeoff comes in response time. Pilot-operated valves typically respond more slowly than direct-acting designs because the pilot signal must first build pressure before the main spool moves. For NG10 (CETOP 5) pilot-operated valves, step response times often extend to 165 milliseconds compared to 100 milliseconds for direct-acting NG6 valves.

Understanding Valve Spool Design and Metering Edges

The heart of proportional control lies in the valve spool design. When you look at a sectional view diagram of a proportional valve, you'll notice the spool has special geometric features that differentiate it from standard switching valve spools.

Proportional directional control valve spools typically feature triangular notches or precisely machined grooves. These notches ensure that flow begins gradually as the spool moves from the center position, providing fine metering characteristics and improved linearity near zero. Without these features, a sharp-edged spool would exhibit abrupt flow changes and poor control at small displacements.

Spool overlap is another critical design parameter often specified in technical diagrams, typically shown as a percentage like 10% or 20%. Overlap refers to how much the spool lands cover the port openings when the valve sits in its center (neutral) position. Controlled overlap helps manage internal leakage and defines the valve's dead band. For example, Parker's D*FW series uses different spool types with B31 offering 10% overlap while E01/E02 types provide 20% overlap.

The dead band represents the amount of control signal required to produce the first spool movement. A valve with 20% dead band needs 20% of the full control signal before the spool begins to move. This dead band must overcome static friction (stiction) forces and relates directly to the spool overlap design. Modern valves with OBE include factory-set dead band compensation that ensures the spool begins moving precisely at minimal electrical input, improving linearity near zero.

Position Feedback with LVDT Sensors

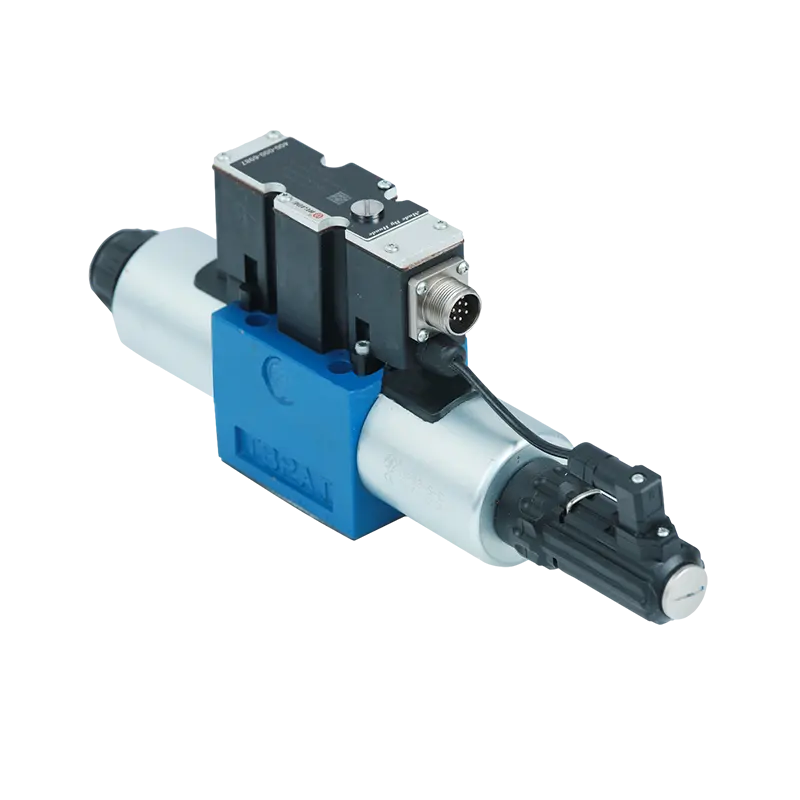

High-performance proportional valves incorporate Linear Variable Differential Transformer (LVDT) sensors for position feedback. When you see an LVDT feedback symbol (often shown as S/U sensor modules) in a proportional valve diagram, you're looking at a closed-loop valve capable of significantly better accuracy than open-loop designs.

The LVDT mechanically connects to the valve spool or armature assembly, continuously measuring the actual physical position. This position signal feeds back to the integrated controller or amplifier, which compares it against the commanded position. The controller then adjusts the solenoid current to maintain the desired spool position, actively compensating for external forces, mechanical friction, and hysteresis effects.

Hysteresis in proportional valves represents an inherent nonlinearity caused primarily by residual magnetism and friction. When you increase the control signal, the valve opens at slightly different points than when you decrease the signal, creating a characteristic loop in the flow-versus-current curve. The width of this hysteresis loop directly impacts control precision.

LVDT feedback addresses this problem by measuring actual spool position rather than inferring it from input current alone. The integrated electronics continuously adjust solenoid current based on the error between measured and commanded positions, effectively canceling positioning errors caused by magnetic hysteresis and friction. This closed-loop control typically reduces hysteresis to below 8% of full range, compared to 15-20% or more for open-loop proportional valves.

Open-Loop vs Closed-Loop Control Architectures

Proportional valve diagrams often appear within larger system schematics showing the complete control architecture. Understanding whether the system uses open-loop or closed-loop control affects both performance expectations and troubleshooting approaches.

In an open-loop motion control system, the electronic controller sends a reference signal to the valve driver (amplifier), and the valve modulates hydraulic parameters based on that signal alone. No measurement of the actual output (flow, position, or pressure) returns to the controller. This simple architecture works adequately for many applications but remains vulnerable to valve drift, load changes, temperature effects, and hysteresis.

Closed-loop motion control systems include an additional feedback sensor measuring the actual output parameter. For a positioning application, this might be a cylinder position sensor (LVDT or magnetostrictive sensor). For pressure control, a pressure transducer provides feedback. The electronic controller, typically implementing PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) regulation, compares the desired setpoint against actual feedback and continuously adjusts the valve command signal to minimize error.

The distinction between valve-level feedback (LVDT on the spool) and system-level feedback (cylinder position sensor) deserves attention. A proportional valve with internal LVDT feedback accurately controls spool position but doesn't directly measure cylinder position or pressure. For highest precision, systems use both: the LVDT ensures accurate valve spool positioning, while external sensors close the loop around the actual process variable (position, pressure, or velocity).

| Feature | External Amplifier / No OBE | Onboard Electronics (OBE) |

|---|---|---|

| Control Signal Input | Variable current or voltage to external board | Low-power voltage/current (±10V, 4-20mA) |

| Physical Footprint | Requires cabinet space for amplifiers | Reduced electrical cabinet space |

| Field Adjustment | Extensive tuning via external board (gain, bias, ramps) | Factory-set tuning ensures high repeatability |

| Wiring Complexity | Complex wiring, may need shielded cables | Simplified installation with standard connectors |

| Valve-to-Valve Consistency | Depends on amplifier calibration | High consistency as amplifier is calibrated to specific valve |

Modern integrated electronics (OBE) significantly simplify system installation. These valves require only standard 24 VDC power and a low-power command signal. The onboard electronics handle signal conditioning, power conversion (often creating ±9VDC working voltage from 24VDC supply), LVDT signal processing, and PID regulation. Factory calibration ensures consistent performance across multiple valves without field tuning, reducing installation time and eliminating variability from external amplifier adjustments.

Performance Curves and Dynamic Characteristics

Technical datasheets for proportional valves include several performance curves that quantify dynamic and steady-state behavior. Understanding how to read these graphs helps in both valve selection and troubleshooting.

The hysteresis curve plots flow rate against control current, showing the characteristic loop that forms when you increase current (opening the valve) versus decreasing current (closing the valve). The width of this loop, expressed as a percentage of total input range, indicates the valve's repeatability. Quality proportional valves achieve hysteresis below 8%, meaning the difference between opening and closing paths spans less than 8% of the full control signal range.

Step response graphs show how quickly the valve reacts to a sudden change in command signal. These typically display valve output (flow or spool position) reaching a specific percentage (often 90%) of a full-step command. For NG6 direct-acting proportional directional valves, typical step response times run around 100 milliseconds, while larger NG10 sizes need approximately 165 milliseconds. Faster response times (8-15 milliseconds for some designs) indicate better dynamic performance but usually come at higher cost.

Dead band characteristics appear on graphs showing the minimum control signal required to produce initial spool movement. A valve with 20% dead band needs one-fifth of full signal before flow begins. This dead band exists to overcome static friction and relates to spool overlap design. Without proper dead band compensation, the valve exhibits poor control resolution near center, making precise positioning difficult.

Contamination and wear directly affect these performance curves in predictable ways. As particles accumulate between spool and bore, static friction increases. This shows up as widening hysteresis loops and increased dead band. By periodically plotting actual flow-versus-current characteristics and comparing them to factory specifications, maintenance teams can detect degradation before it causes system failures. When hysteresis exceeds specified limits by 50% or more, the valve typically needs cleaning or replacement.

| Characteristic | NG6 Interface | NG10 Interface | Engineering Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step Response (0 to 90%) | 100 ms | 165 ms | Time to achieve dynamic flow/pressure changes |

| Maximum Hysteresis | <8% | <8% | Deviation between increasing and decreasing signal |

| Repeatability | <2% | <2% | Output consistency for given input across cycles |

| Max Operating Pressure (P, A, B) | 315 bar (4,500 PSI) | 315 bar (4,500 PSI) | System design constraint for safety and longevity |

System Integration and Application Circuits

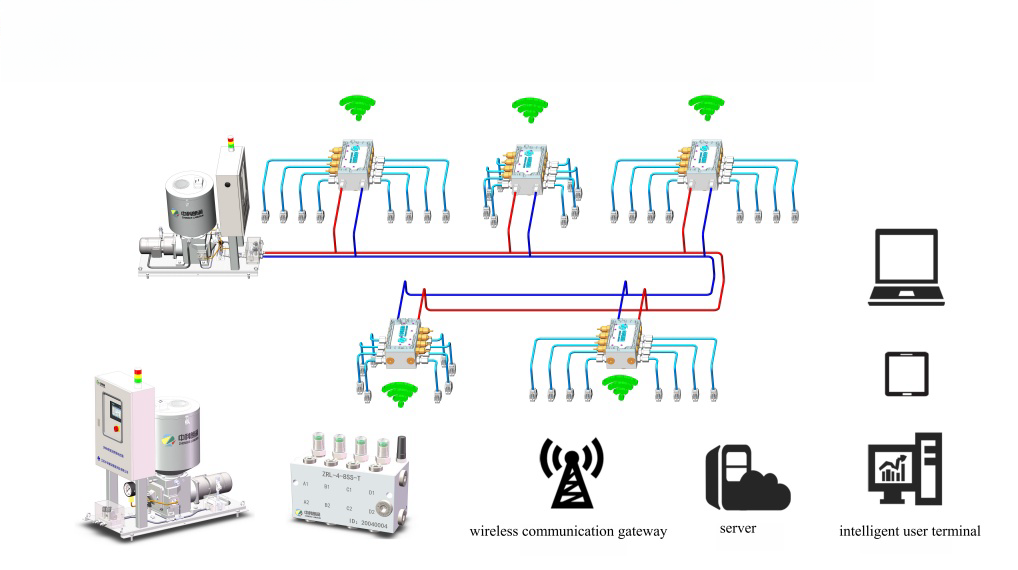

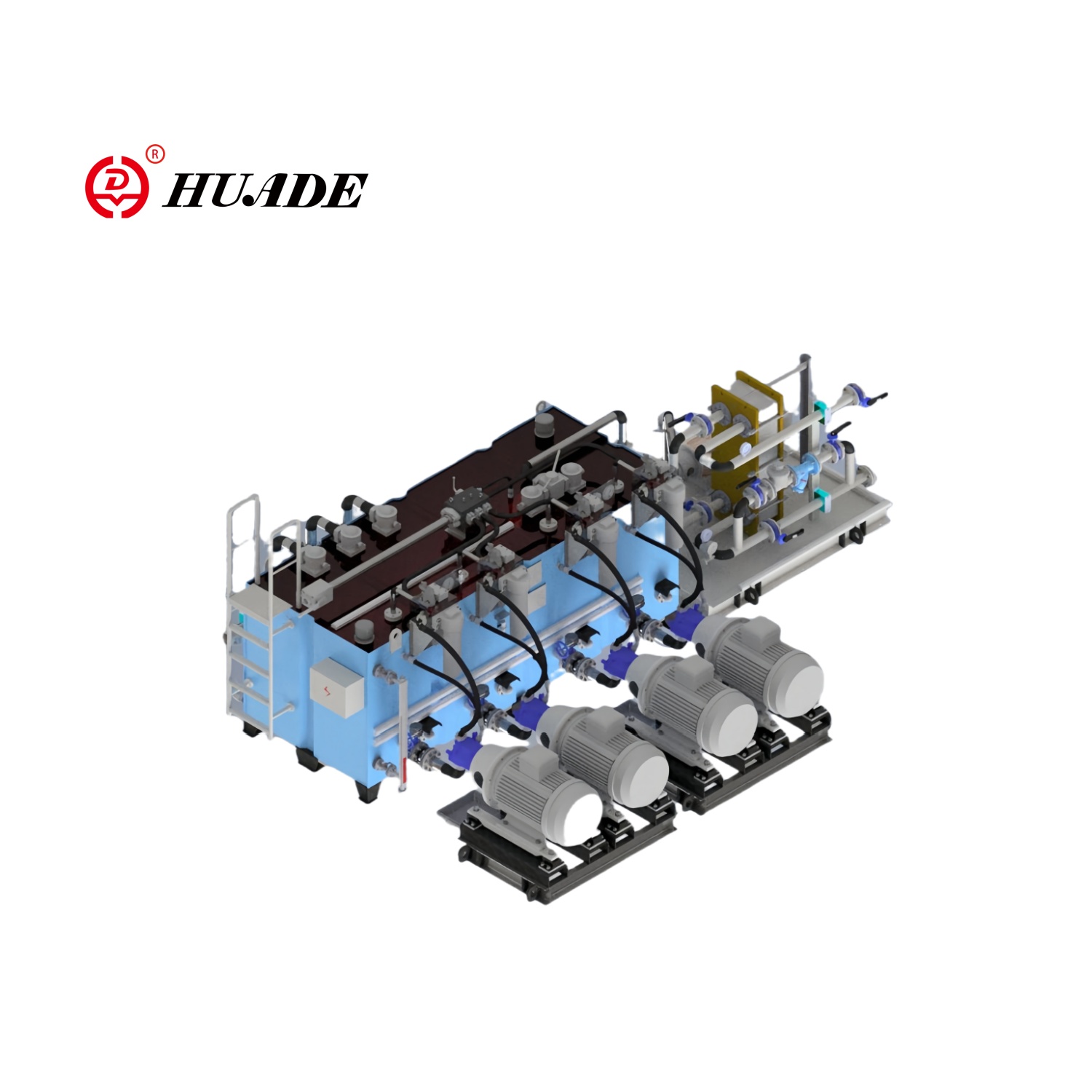

Proportional valve diagrams reach their full meaning when viewed within complete hydraulic circuits. A typical closed-loop hydraulic positioning system diagram includes the power unit (pump and reservoir), the proportional directional control valve, a hydraulic cylinder as the actuator, and a position sensor providing feedback.

``` [Image of hydraulic circuit diagram with proportional valve] ```Circuit diagrams show pressure drops at valve ports (often labeled as ΔP₁ and ΔP₂), illustrating how flow metering controls force balance on the actuator. For a cylinder with 2:1 area ratio (different piston and rod-end areas), the valve must account for differential flow requirements during extension versus retraction. The proportional valve diagram indicates which port configurations achieve smooth motion in both directions.

In injection molding applications, hydraulic proportional valves precisely control clamping force, injection velocity, and pressure profiles throughout the molding cycle. These applications require multiple proportional valves working in coordinated sequences, reflected in complex circuit diagrams showing pressure control valves for clamping, flow control valves for injection speed, and directional control for mold movement.

Mobile equipment like cranes and movable bridges use closed-loop hydraulic systems where proportional valves control variable displacement pump output. By adjusting pump displacement rather than dissipating energy through throttling valves, these systems achieve higher efficiency. The circuit diagrams typically show a charge pump maintaining 100 to 300 PSI in the low-pressure leg of the main circuit, with proportional valves managing direction, acceleration, deceleration, speed, and torque without separate pressure or flow control elements.

Energy efficiency considerations heavily influence circuit design philosophy. Traditional proportional directional control valves achieve control through throttling, which converts hydraulic energy to heat across the metering orifices. This dissipative control provides excellent control fidelity but requires adequate fluid cooling capacity. In contrast, variable displacement control minimizes energy waste by adjusting the source rather than dissipating excess flow through relief valves. Designers must balance the simplicity of throttling control against the efficiency gains from variable displacement approaches.

Troubleshooting Proportional Valve Systems

Performance degradation in proportional valves typically manifests as changes in the characteristic curves discussed earlier. Understanding these failure modes helps establish effective diagnostic procedures.

Contamination represents the most common cause of proportional valve problems. Particles as small as 10 micrometers can interfere with spool movement, causing stiction (high static friction) that requires increased initial current to overcome. This appears as increased dead band and widened hysteresis loops. Maintaining hydraulic fluid cleanliness according to ISO 4406 cleanliness standards (typically 19/17/14 or better for proportional valves) prevents most contamination-related failures.

Drift and leakage issues stem from seal wear or internal valve wear. As seals degrade, internal leakage allows actuators to drift even when the valve sits centered. Temperature affects seal performance dramatically. High temperatures thin the fluid and degrade seal materials, while low temperatures increase viscosity and reduce seal flexibility, both causing control problems.

Spring fatigue from continuous cycling and thermal exposure manifests as slow or incomplete return to center position. The centering springs that return the spool to neutral gradually lose force over millions of cycles, requiring eventual replacement or valve refurbishment.

A systematic troubleshooting flowchart typically begins with electrical verification. Check power supply voltage (usually 24 VDC ±10%), command signal levels, and wiring integrity. Measure solenoid resistance to detect coil failures. For valves with OBE, many models provide diagnostic outputs indicating internal faults.

Mechanical diagnosis involves pressure testing at valve ports. Large pressure drops across the valve (beyond specifications) indicate blockage or internal wear. Flow measurement helps verify that actual flow matches system requirements at given control signals. Temperature monitoring identifies overheating from excessive throttling or inadequate cooling.

Predictive maintenance programs should include periodic performance verification. By plotting actual flow-versus-current characteristics annually and comparing them to baseline measurements, maintenance teams can track gradual degradation. When measured hysteresis increases by 50% above original specification, schedule valve cleaning or replacement during the next maintenance window rather than waiting for complete failure.

Selecting the Right Proportional Valve

When you're designing a system or replacing components, proportional valve selection requires balancing several technical parameters against cost and space constraints.

- Flow capacity comes first. Calculate required actuator velocity and multiply by piston area to determine flow rate. Add a safety margin (typically 20-30%) and select a valve with rated flow at or above this requirement. Remember that valve flow capacity varies with pressure drop across the valve; always check flow curves at your operating pressure differential.

- Pressure rating must exceed maximum system pressure with adequate safety margin. Most industrial proportional valves handle 315 bar (4,500 PSI) on main ports, sufficient for typical mobile and industrial hydraulics. Higher pressure applications may require servo valves or specialized proportional designs.

- Control signal compatibility matters for system integration. Most modern valves accept either voltage (±10V) or current (4-20mA) signals. Voltage signals work well for short cable runs while current signals resist electrical noise over longer distances. Verify your controller output matches the valve input requirements or plan for appropriate signal conversion.

- Response time requirements depend on your application dynamics. For slow-moving equipment like presses or positioning stages, 100-150 millisecond response suffices. High-speed applications like injection molding or active suspension systems may need servo valves with sub-20 millisecond response instead.

- Environmental considerations include operating temperature range, vibration resistance, and mounting orientation. Valves with OBE offer superior vibration resistance since the electronics mount directly to the valve body, eliminating vulnerable cable connections between valve and amplifier. Operating temperature typically ranges from -20°C to +70°C for standard designs, with specialized versions available for extreme conditions.

The Future of Proportional Valve Technology

Proportional valve technology continues evolving toward higher performance and smarter integration. Modern designs increasingly incorporate advanced diagnostics, providing real-time health monitoring and predictive maintenance capabilities. Communication protocols like IO-Link allow proportional valves to report detailed operational data including cycle counts, temperature, internal pressure, and detected faults.

The convergence between proportional and servo valve performance continues. As proportional valve manufacturers improve spool machining precision and implement advanced control algorithms in OBE systems, the performance gap narrows. For many applications that once mandated expensive servo valves, modern proportional valves with LVDT feedback now deliver adequate precision and repeatability at significantly lower cost.

Energy efficiency drives innovation in both component and system design. New valve geometries minimize pressure drops while maintaining control precision, reducing heat generation and power consumption. System-level improvements include intelligent control strategies that coordinate multiple proportional valves to optimize overall energy use rather than controlling each valve independently.

Understanding proportional valve diagrams provides the foundation for working effectively with modern automated equipment. Whether you're designing new systems, troubleshooting existing installations, or selecting components for upgrades, the ability to interpret these standardized symbols and their implications gives you critical insight into system behavior and performance characteristics. The diagrams represent not just static component symbols but encapsulate decades of engineering refinement in electro-hydraulic control technology.