What Are Hydraulic Sequence Valves and Why Do They Matter?

A hydraulic sequence valve is a pressure control component that enforces a strict operational order in multi-actuator systems. Unlike relief valves that protect systems from overpressure, sequence valves act as logic gates - they block flow to a secondary circuit until the primary circuit reaches a preset pressure threshold.

Think of it this way: In a machining operation, you need the workpiece clamped with 200 bar of force before the drill bit engages. A sequence valve ensures the hydraulic system cannot physically start drilling until that 200 bar clamping pressure is confirmed. This isn't just about timing - it's about force verification.

The core distinction here is critical for engineers: Position-based control (using limit switches) verifies where an actuator is, but pressure-based control (using sequence valves) verifies how much force the actuator has actually generated. In applications like metal forming, welding fixtures, or press operations, this force guarantee is non-negotiable for both safety and process quality.

How Sequence Valves Work: The Force Balance Mechanism

Basic Operating Principle

The sequence valve operates on a straightforward force balance equation:

Where:

- PA = Inlet pressure (primary circuit)

- Aspool = Effective area of the valve spool

- Fspring = Pre-set spring force

- Pdrain = Backpressure in the drain/spring chamber

The Three-Stage Operating Sequence:

- Stage 1 - Primary Circuit Activation: Pump flow enters Port A and drives the primary actuator (e.g., a clamping cylinder). The valve's main spool remains closed, blocking flow to Port B.

- Stage 2 - Pressure Buildup: As the primary actuator completes its stroke or encounters resistance, pressure at Port A rises. The hydraulic force acting on the valve spool increases proportionally.

- Stage 3 - Valve Shifting & Secondary Circuit Release: When PA reaches the cracking pressure (typically 50-315 bar depending on spring setting), the spool shifts against the spring. This opens an internal passage, redirecting flow from Port A to Port B, which then activates the secondary actuator (e.g., a feed cylinder).

Pilot-Operated vs. Direct-Acting Designs

For high-flow applications (>100 L/min), manufacturers use pilot-operated designs rather than direct-acting types. Here's the engineering rationale:

In a direct-acting valve, the main spool is controlled directly by the spring and inlet pressure. This requires a very stiff, high-force spring to handle large flow forces, making the valve bulky and difficult to adjust accurately.

A pilot-operated sequence valve uses a two-stage design:

- A small pilot poppet (controlled by a low-force adjustable spring) senses Port A pressure

- When pilot pressure reaches setpoint, it opens and depressurizes the main spool's control chamber

- This allows the much larger main spool to shift with minimal force

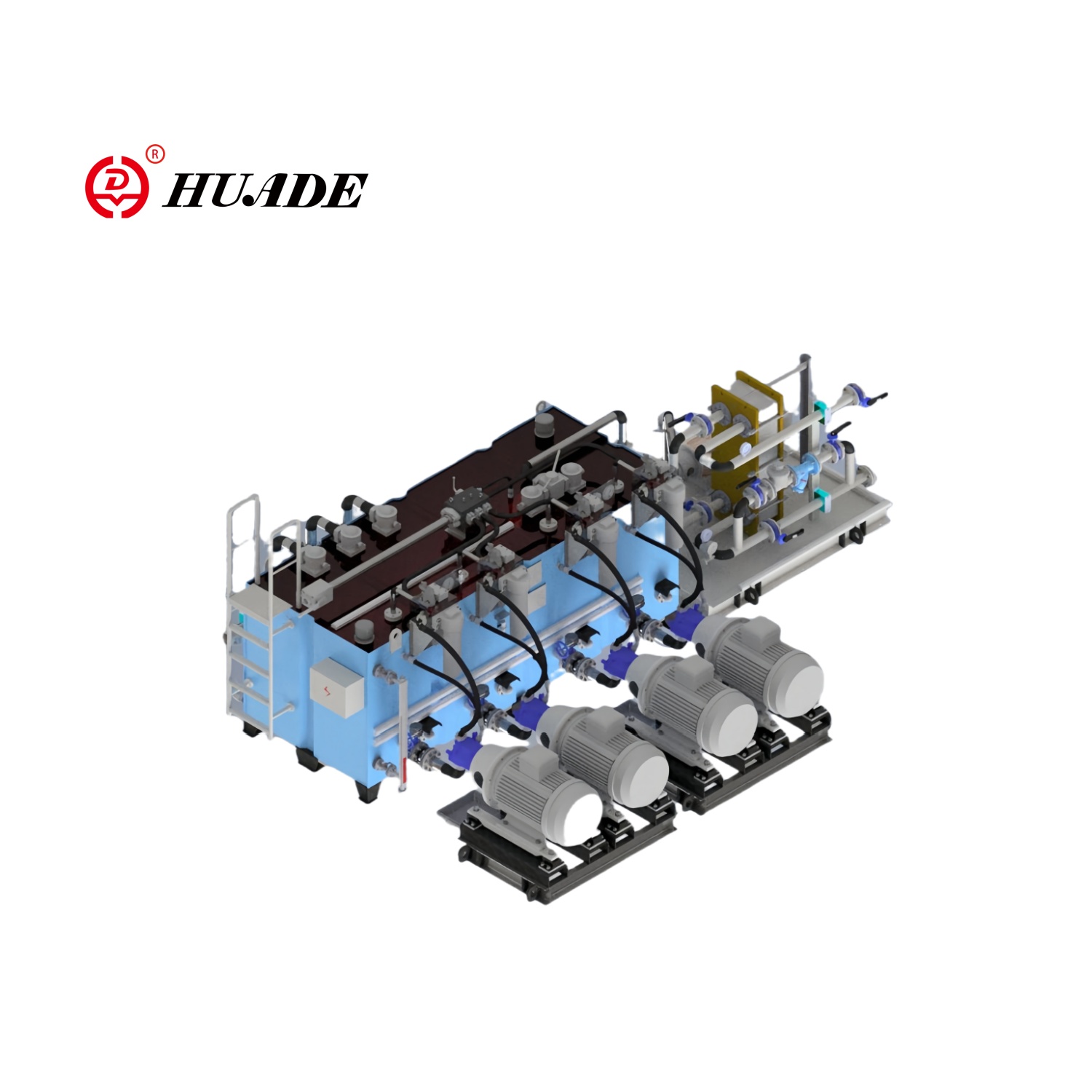

Practical Advantage: A pilot-operated valve can handle 600 L/min at 315 bar while still using a hand-adjustable spring for pressure setting. Models like the DZ-L5X series achieve this with flow capacities from NG10 (200 L/min) to NG32 (600 L/min).

Configuration Types: Control and Drain Path Variations

The behavior of a sequence valve fundamentally depends on where the control signal comes from and where the spring chamber drains. This creates four distinct configurations:

| Configuration Type | Control Signal Source | Drain Path | Cracking Pressure Formula | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Control, External Drain (Most Common) | Port A (inlet) pressure | Tank (Y port) - nearly 0 bar | Pset = Fspring only | Standard sequencing where precise, load-independent pressure setting is required |

| Internal Control, Internal Drain | Port A (inlet) pressure | Port B (outlet) | Pset = Fspring + PB | Applications where downstream pressure PB is stable and predictable |

| External Control, External Drain | Port X (remote pilot) | Tank (Y port) | Pset based on PX | Complex interlocking circuits requiring external trigger signals |

| External Control, Internal Drain | Port X (remote pilot) | Port B (outlet) | Complex - depends on PX and PB | Rare - specialized load-holding or balance applications |

Critical Design Rule for External Drain

For 90% of sequencing applications, you must use External Drain (Y port to tank) configuration. Here's why:

If you mistakenly use internal drain and the downstream circuit (Port B) has varying pressure - say it fluctuates between 20-80 bar due to load changes - your cracking pressure becomes:

This 60 bar swing in cracking pressure destroys the entire logic of force-verification sequencing. The valve might trigger prematurely under light loads or delay under heavy loads. Always route the Y drain directly to tank unless you have a specific engineering reason documented in the hydraulic schematic.

Sequence Valve vs. Relief Valve: Why Structure Similarity Masks Functional Difference

This is one of the most searched comparisons - and for good reason. Both valves use spring-loaded spools and respond to pressure. But confusing their roles can lead to catastrophic system design errors.

| Characteristic | Sequence Valve | Relief Valve |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Flow redirection - routes fluid to secondary circuit after pressure threshold | Pressure limiting - dumps excess flow to tank to prevent overpressure |

| Normal Operating State | Opens temporarily then closes after sequence completes | Opens continuously when system exceeds setpoint |

| Outlet Port (B) Function | Sends flow to work circuit (useful flow) | Sends flow to tank (wasted energy/heat) |

| Precision Requirement | High - must trigger at exact force verification point (±5 bar tolerance) | Moderate - just needs to prevent damage (±10-15 bar acceptable) |

| System Role | Control logic element - determines when actions occur | Safety device - prevents if conditions exceed limits |

| Can Replace Each Other? | NO - A relief valve would waste energy continuously; a sequence valve won't protect from overpressure | |

Real-World Analogy:

A relief valve is like a pressure relief valve on a pressure cooker - it vents steam (to waste) when pressure gets dangerously high.

A sequence valve is like a safety interlock on a lathe - it prevents the spindle from starting until the chuck guard is confirmed closed. It's enforcing order, not just limiting pressure.

One-Way Sequence Valves: Solving the Return Flow Problem

Standard sequence valves create a problem during the return stroke: if the secondary actuator's return flow must pass back through the sequence valve, it encounters the full cracking pressure resistance.

Example: Your sequence valve is set to 180 bar. During retraction, even if you only need 20 bar to pull the cylinder back, you'd need to overcome 180 bar to get flow through the valve in reverse. This causes:

- Extremely slow retraction speeds

- Massive heat generation (wasted 160 bar × flow)

- Potential cavitation at the actuator

Solution: Integrated Check Valve

A one-way sequence valve incorporates a parallel check valve (sometimes called a bypass check) that allows free reverse flow from Port B to Port A. The check valve typically has a cracking pressure of only 0.5-2 bar, meaning:

- Forward direction (A→B): Full sequence valve logic applies (180 bar cracking)

- Reverse direction (B→A): Check valve bypasses main spool (2 bar cracking)

This is mandatory in circuits where the secondary actuator must retract through the same valve. Manufacturers provide ΔP vs. Flow curves for the check valve path - verify this at your maximum return flow rate to ensure acceptable pressure drop.

Application Example: Drill Press Clamp-Then-Feed Circuit

Let's walk through a classic application that demonstrates why sequence valves are irreplaceable in precision work:

The Requirement

A vertical drill press must:

- Clamp the workpiece with minimum 150 bar force

- Drill the workpiece only after clamping is verified

- Retract the drill

- Unclamp the workpiece

Why Position Control Fails Here

If you used a limit switch on the clamp cylinder, it would trigger when the cylinder touches the workpiece - but before any actual clamping force builds up. A warped workpiece or loose fixture would result in the drill advancing into an un-clamped part, causing:

- Workpiece ejection (safety hazard)

- Broken drill bits

- Scrap parts

Sequence Valve Circuit Design

Components:

- SV1: Sequence valve (setpoint: 150 bar) in clamp circuit

- Clamp Cylinder: 50mm bore

- Feed Cylinder: 32mm bore

- Pressure Relief: 200 bar (system safety)

Operating Logic:

- Directional valve energizes: Flow enters clamp cylinder through Port A of SV1

- Clamp extends: Cylinder advances until workpiece contact. Pressure at Port A begins rising.

- Pressure buildup: When clamp force reaches 150 bar (equivalent to ~2,950 kg clamping force for 50mm bore), SV1 opens.

- Feed cylinder activates: Flow now diverts to Port B of SV1, advancing the drill feed cylinder.

- Force maintained: The clamp stays pressurized at 150+ bar throughout drilling.

The Critical Insight: The system cannot physically drill until sufficient clamping force exists. This is hardware-based safety - no software logic or sensor can fail to bypass it.

Selection Criteria: Matching Valve to Application

1. Pressure Range Specification

Sequence valves are available in multiple pressure range settings, typically:

- Low range: 10-50 bar (soft clamping, delicate parts)

- Medium range: 50-100 bar (general assembly)

- High range: 100-200 bar (forming, pressing)

- Extra high range: 200-315 bar (heavy stamping, forging)

Selection Rule: Choose a valve whose adjustment range spans your target setpoint. If you need 180 bar, select a 100-200 bar or 150-315 bar range valve. Don't use a 50-315 bar valve - the spring will be too stiff for fine adjustment at the high end.

2. Flow Capacity vs. Pressure Drop

The valve must pass your maximum instantaneous flow without excessive pressure drop. Manufacturers provide Q-ΔP curves showing pressure loss at various flow rates.

Example Specification:

- Required Flow: 120 L/min

- Acceptable ΔP: <10 bar (to minimize energy waste)

- Selected Valve: NG20 (rated 400 L/min) - provides 5-6 bar ΔP at 120 L/min

Common Mistake: Selecting a valve sized exactly for nominal flow. This ignores the pressure drop that increases exponentially at high flows. Always size at least 150% of nominal flow for smooth operation.

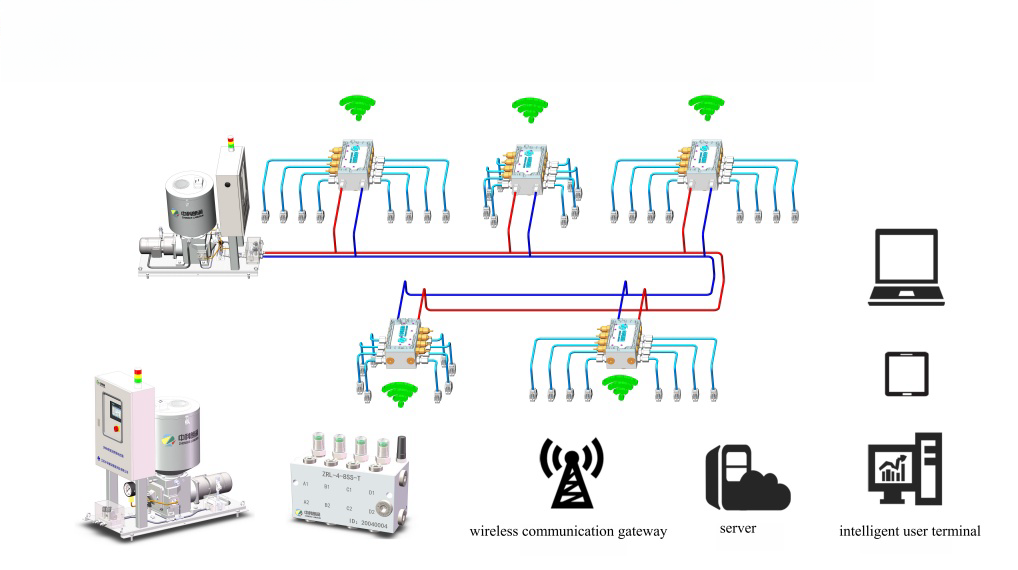

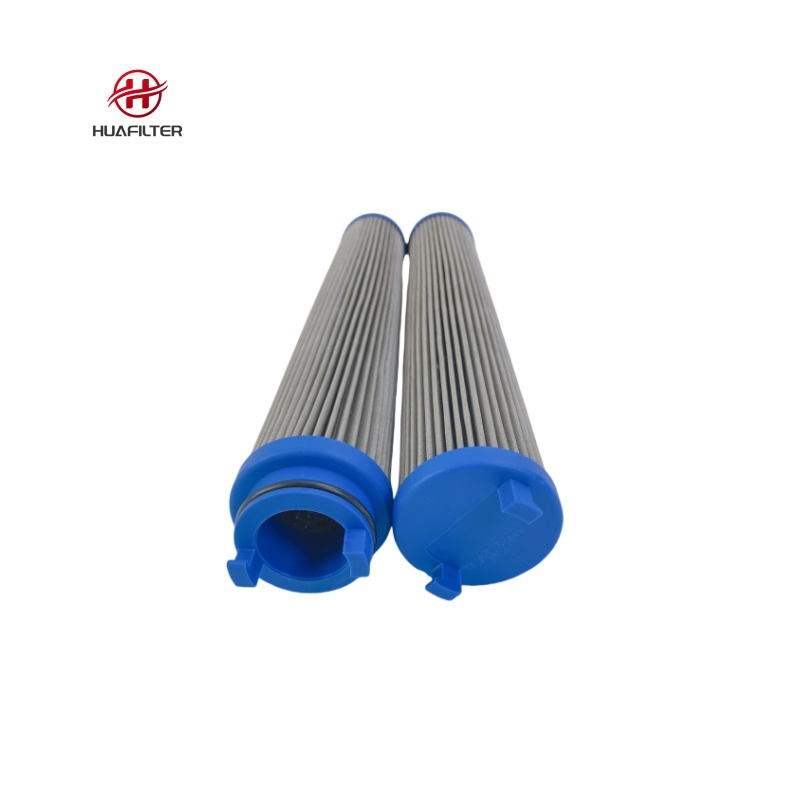

3. Fluid Cleanliness Requirements

This is where many field failures originate. Pilot-operated sequence valves have internal orifices and control lands with clearances as tight as 5-10 microns. The spring chamber control passages are even more sensitive.

Mandatory Contamination Specification:

- ISO 4406: 20/18/15 or better

- NAS 1638: Class 9 or better

Translation: Your hydraulic oil must have:

- Fewer than 20,000 particles >4μm per 100ml

- Fewer than 4,000 particles >6μm per 100ml

- Fewer than 640 particles >14μm per 100ml

Practical Implementation:

- Install 10-micron absolute filtration (β₁₀ ≥ 200) on return line

- Use 3-micron filters on pilot drain lines (if external drain)

- Implement oil analysis every 500 operating hours (particle count, water content, viscosity)

If contamination exceeds limits, expect:

- Spool sticking (valve fails to open or close)

- Pressure drift (internal wear increases leakage)

- Hunting/oscillation (erratic pilot operation)

4. Installation Interface Standards

Sequence valves mount to subplates or manifolds per industry standards:

| Valve Size (NG) | Mounting Standard | Bolt Size | Torque Spec | Surface Finish Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NG06 | ISO 5781 (D03) | M5 | 6-8 Nm | Ra 0.8 μm |

| NG10 | ISO 5781 (D05) / DIN 24340 | M10 | 65-75 Nm | Ra 0.8 μm |

| NG20/NG25 | ISO 5781 (D07) | M10 | 75 Nm | Ra 0.8 μm |

| NG32 | ISO 5781 (D08) | M12 | 110-120 Nm | Ra 0.8 μm |

Critical Installation Rule: The mounting surface flatness tolerance must be 0.01mm per 100mm. Use a precision ground surface plate to verify. Any warping causes O-ring extrusion under 315 bar pressure, leading to external leakage.

Troubleshooting Common Failures

| Symptom | Probable Root Cause | Diagnostic Check | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valve opens too early (premature shifting) |

1. Spring fatigue/failure 2. Incorrect drain configuration 3. Pilot orifice erosion |

1. Measure cracking pressure with gauge 2. Verify Y port drains to tank 3. Check pilot adjustment screw position |

1. Replace spring assembly 2. Reconfigure to external drain 3. Replace pilot section or full valve |

| Valve won't open (no secondary flow) |

1. Spool seized by contamination 2. Pilot chamber clogged 3. Adjustment set too high |

1. Check oil ISO cleanliness 2. Remove pilot cover, inspect orifice 3. Verify adjustment vs. system pressure capability |

1. Clean/flush system, replace filters, possibly replace valve 2. Ultrasonic clean pilot parts 3. Reduce setpoint or increase pump pressure |

| Severe vibration/chattering noise |

1. Oversized pilot control volume 2. Air in control chamber 3. Resonance with pump pulsation |

1. Check length of pilot lines (X, Y) 2. Bleed system thoroughly 3. Measure vibration frequency vs. pump RPM |

1. Use compact manifold mount, minimize line length 2. Install bleeder valves at high points 3. Install pulse damper or change pump speed |

| Pressure setting drifts over time |

1. Thermal expansion of spring 2. Wear causing internal leakage 3. Seal degradation |

1. Monitor pressure at different oil temps 2. Measure leakage from drain port 3. Inspect for external weeping |

1. Use temperature-compensated design or control oil temp 2. Replace worn spools/bores 3. Replace seals with correct material (NBR for mineral oil, FKM for phosphate ester) |

| External leakage at mounting face |

1. O-rings damaged or wrong material 2. Mounting surface not flat (>0.01mm/100mm) 3. Improper bolt torque |

1. Inspect O-rings for cuts, swelling 2. Check surface with dial indicator 3. Use torque wrench to verify spec |

1. Replace O-rings (match fluid type) 2. Re-machine or lap mounting surface 3. Torque bolts to 75 Nm (M10) in star pattern |

The Contamination Cascade Failure

Here's a typical failure sequence seen in industrial systems:

Month 1-6: Oil contamination slowly rises from ISO 18/16/13 (acceptable) to 21/19/16 (marginal). No symptoms yet.

Month 7: Spool starts exhibiting stiction (stick-slip behavior). Pressure setpoint becomes erratic - sometimes 175 bar, sometimes 195 bar. Production reports "random" rejections.

Month 8: Maintenance increases adjustment to compensate for perceived "weak spring." Now set to 210 bar. Primary actuator starts overheating (excessive clamping force).

Month 9: Internal wear from particles accelerates. Leakage increases. Valve now "hunts" - opens and closes rapidly, creating hydraulic shocks. Downstream hoses start failing.

Month 10: Catastrophic failure - spool jams fully open. No sequencing control. Secondary actuator activates with primary at zero pressure. Equipment crash or workpiece ejection.

Root Cause: Single decision to extend filter change interval from 1,000 to 1,500 hours to "save costs."

Prevention: Rigorous adherence to ISO 20/18/15 cleanliness through proper filtration and quarterly oil sampling.

Key Takeaways for System Designers

- Sequence valves verify force, not position. Use them when clamping force, pressing force, or load-holding is safety-critical.

- External drain configuration (Y to tank) is mandatory for 90% of applications to achieve stable, load-independent pressure settings.

- Pilot-operated designs are essential for flows >100 L/min. They offer better adjustability and lower operating forces than direct-acting types.

- Fluid cleanliness is non-negotiable. Specify ISO 20/18/15 and implement 10-micron absolute filtration as minimum. Budget for quarterly oil analysis.

- One-way valves are not optional in circuits where the secondary actuator must retract through the valve. The integrated check valve prevents massive energy waste.

- Size for 150% of nominal flow to keep pressure drop under 10 bar. This improves efficiency and reduces heat generation.

- Installation surface precision matters. A warped subplate causes O-ring failure under high pressure. Verify 0.01mm/100mm flatness.

When properly selected, installed, and maintained, hydraulic sequence valves provide decades of reliable service in enforcing the operational logic that keeps automated systems safe and productive.